From Zines to Screens: Blending Technologies to Publish Your Work

From Zines to Screens: Blending Technologies to Publish Your Work

One of the hardest questions to ask and get an answer to is “What is my work for?”

Just a few possible personal answers to this for me are:

To create something new

To share my artistic self

To learn to make things

To engage with art tools

To meet friends

To attract mates

For revenge

To explore humanity, mine and others

To deepen one’s humanity

To discover internal resources and to devote them to transcending survival mode

To surpass my own limits

To learn a craft, any craft

To commune with natural processes (ink is largely carbon and water; paper is wood pulp.)

To be part of a tradition

To create and return to a ritual space

To annoy people

To impress people

To let me be me

To say, I was here.

You get the idea.

These form a sort of range from the social (meet friends, attract mates, revenge) to the personal mechanical development (learn a craft, engage with art tools) to the spiritual or semi-spiritual (to return to a ritual space, to discover internal resources), etc.

These answers are of course constantly blending. And with technology, the tools by which we make our work to serve these purposes are constantly changing.

I was raised knowing that the primary tool of my comics was ink, and the tools to get it on paper were primarily dip pens, technical pens, and markers.

Comics were black and white except when an extra expense could be justified, then they would be in color.

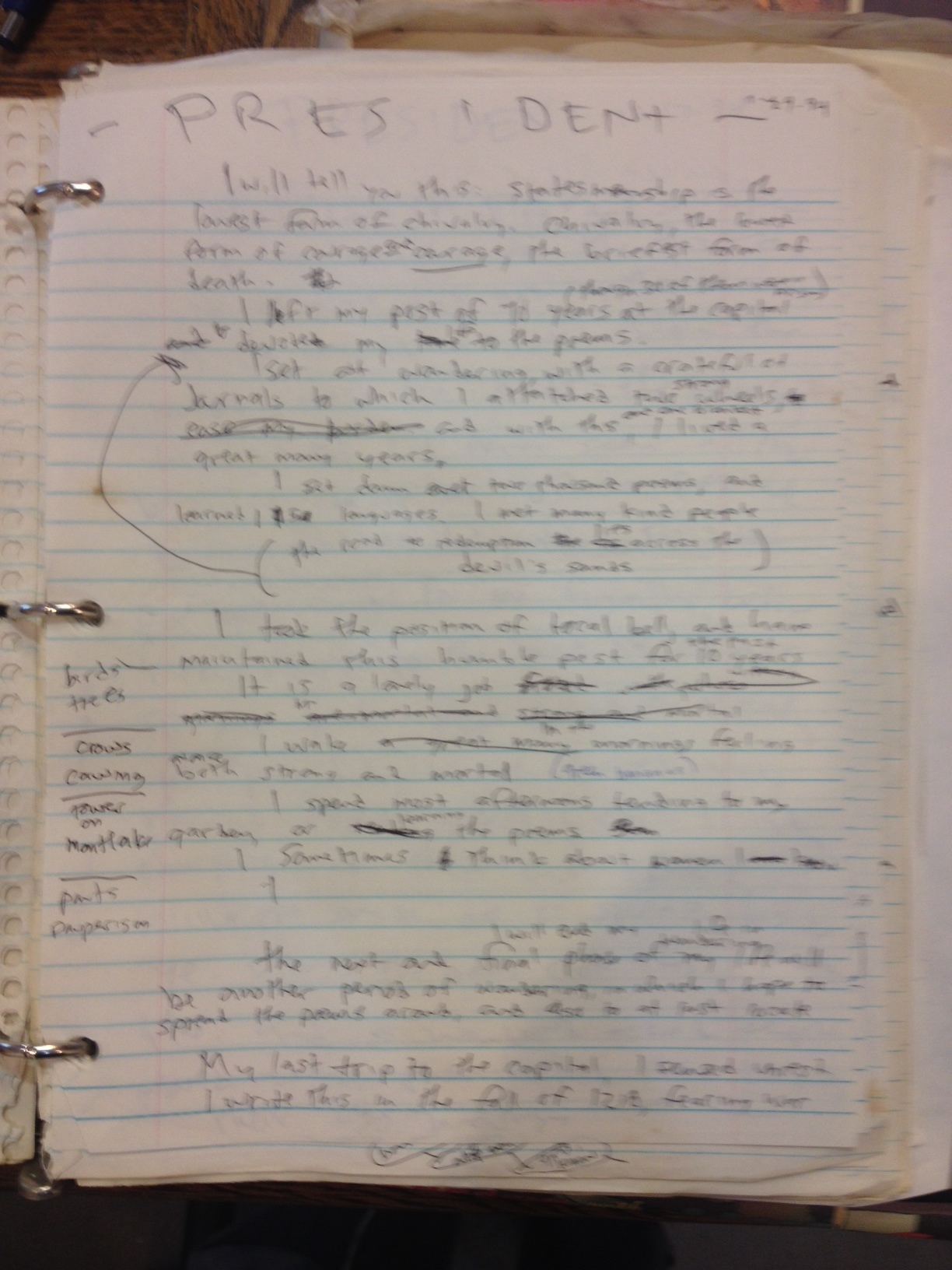

Often I began with ideas in pencils or ballpoint pen. Following my thoughts the way I learned in school- on lined paper, one thought after another.

And then drawing. I learned to love drawing in ink. It gave me what I wanted, which as a young artist, was largely the social desires of art, to meet people, to impress people, but also to understand humanity. Along with the ballpoint pen and paper, ink was one of the tools I used to interpret the world.

The photocopier was the next step. (Though perhaps I’m skipping scissors and gluestick.) With the photocopier, I could distribute my work, send it to people, meet more people, find my tribe, and say I was here.

The remarkable thing was how profound art making came to become for me, and how ancillary everything else became, even when they gave me the same goals: at parties I could meet people, at art fairs I could distribute the work, to readers who would know that I was here.

So what was different? What was different was I enjoyed art making, and it gave me deeper things. It connected me to my better self, it game a connection to silence, and my better thoughts and feelings. It allowed me to interpret the world and humanity more than I knew.

So I drew and drew more comics, still in ink with almost archaic sheets of shading film, and I even began to create with the photocopier, incorporating more collage into my work, especially the covers.

I graduated from photocopiers to offset printers, which work from photographic plates and enormous machines printing hundreds to thousands of copies at a time, cutting enormous sheets of paper into 16-page signatures which together combine into 48, or 64 page books. (I didn’t operate these machines, I sent my work to people who knew how to operate them, or to people who knew people who knew how to operate them.)

When the books were being printed, the artistic part of the job was done. My dealings with the technology was finished too. I provided the ideas, the ink on paper, the envelope and the stamp.

Readers today will know where this is heading. Desktop computers and Adobe Photoshop came along next, and soon books were finalized and prepped on them, and soon they were cleaned-up and distributed them, and eventually 100% created and submitted and distributed via computer.

So everything is faster and easier. We can undo mistakes. We can meet the social goals of art easier than ever. So easy that it’s easy to forget the other goals.

And now the new technologies raise other questions:

Are we engaging with tradition when we move from brush and ink to digital emulators of brush and ink, or are we subverting that tradition?

Can a ritual space be flat and instant, like a computer?

Am I surpassing my own limits if I let the computer handle so much of it? If I can “undo”?

Are we losing touch with our humanity when we forego 3-D tools, which humanity has worked with for 200,000 years, or are we deepening it?

Everyone has to answer these questions for themselves. And they still need to be asking, constantly, because technology is changing constantly, What is my art for?

I run a comics art school, and I’m old school, so I insist that the students learn ink.

Why?

To engage with the tradition, to engage with art tools and to learn a craft, any craft. It’s NOT the best way to meet the social goals of art any more. It’s not the best way to meet people, it’s not necessarily the best way to “explore humanity.”

When I ask myself that main question still, I find the answers constantly shifting, and in the work I am creating, now 30 years after my first photocopied mini-comic, I don’t always know the answers.

Next: B. Is Dying